Dance Manuals

The primary sources for learning about the details of how dancing masters taught dancing and social etiquette in the nineteenth century are printed dance manuals. Most of these manuals follow the same pattern: first, a chapter on the history of dance; second, manners in general; and last, a description of the current dances.

It is likely that Mr. Macindoe’s students began their training with the study of the fundamental principles of ballroom dancing which included correct physical deportment, walking, and salutations, i.e. introduction and the bow. These basic exercises assisted the student in balance and form, which led to freedom of movement while dancing.

These exercises were an important factor in the acquisition of social graces. Socially, correct and elegant physical deportment was an indispensable asset. To move with refinement was the mark of a cultured person and was required of anyone who wanted to be accepted in polite society. Command of one’s posture was an outward expression of all forms of good manners. Therefore, it was a vital part of the dancing master’s responsibility to devote special attention to teaching his students how to stand well. The idea was not to exaggerate posture, but to be natural and perfectly at ease.

The carriage of the body while dancing was another sign of how well one had mastered the etiquette of the ballroom. In the nineteenth century, ballroom dances had either a vertical body carriage, as in the waltz, or they leaned toward the direction of travel, for example, in the polka. Study under a competent dancing master was needed to acquire this proper ballroom etiquette.

The fortitude needed to learn the correct ballroom decorum, and the execution of the many and varied dance steps encouraged self-discipline and perseverance which led to a strengthening of one’s moral character. Rules encouraged responsibility, which was a quality appropriate to an honourable person who behaved with self-control and moderation. In Hamilton the upper class would have been concerned that the standard of manners and morals remain steady in order that they could continue to differ socially and qualitatively from the lower class.

All the upper class balls and assemblies had rules that followed a specific procedure, and it was the responsibility of the dancing master to prepare his students to follow these rules. Etiquette at balls and assemblies was administered by stewards appointed by a committee of the sponsoring organization. It was their duty to see that the procedure was conducted in the proper manner. The rules were very specific; for example, if a gentleman would like to dance with a particular lady who was not his partner, or a lady he did not know well, it was his responsibility to approach a steward, and indicate (discreetly) the lady he would like to take as a dancing partner. If there was no inequality of rank, the steward would present the gentleman to the lady, and if the lady objected (which was her privilege) the steward would probably select someone more suitable. On no account was it proper for a gentleman to approach a lady without the assistance of a steward unless the lady was a relative or his partner for the evening.

The manners used in the ballroom were carried over into everyday activities. Any lady a gentleman danced with at an assembly or ball could not to be claimed as an acquaintance later. This meant that should the gentleman meet the lady the next day, or at some future time, it was not his privilege to attempt to address her. At most, he was permitted to lift his hat, but even this would be better avoided unless the lady first bowed slightly.

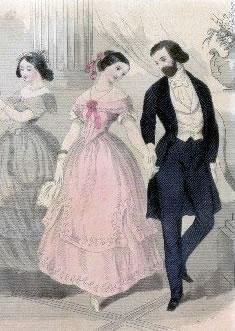

Another important facet of ballroom etiquette involved wearing the proper clothing, which was seen as an essential part of having good manners. Ladies were advised to wear a dress of a light shade, or a white silk properly trimmed with tulle or flowers. Young ladies wore lightweight materials, and it was necessary for every lady to wear an opera cloak and perfectly fitted white kid gloves which were never to be removed. A second pair of gloves was to be carried in the purse for emergency use.

The correct gentleman’s wardrobe consisted of black dress coat, black trousers and a black or white vest, a white necktie, white kid gloves, and patent leather boots. All clothing was to be of the finest quality.

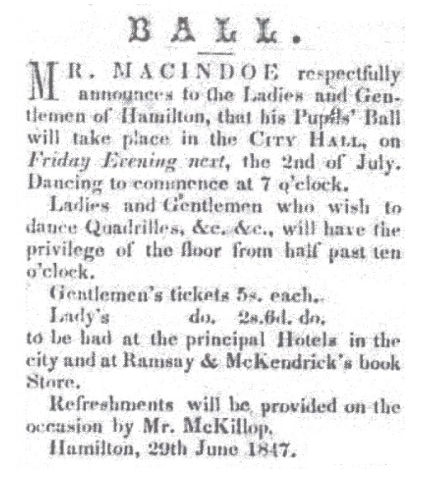

For the dance student the ultimate test took place at the conclusion of the term when the dancing master gave his customary ball. Mr. Macindoe held his end-of-term ball in Hamilton’s Town Hall, and newspaper reviews indicate that they were always supported by a large and enthusiastic audience consisting of family and friends.

Mr. Macindoe’s Ball: – the Ball with which Mr. Macindoe usually entertains his pupils at the close of his term of teaching, came off in the Town Hall on Friday night last, and the scene was unusually interesting. About 150 individuals were present on the occasion, and all seemed delighted with the performance of the dancers, and agreeably surprised at the knowledge they had acquired of the fashionable exercises . . . The whole proceedings of the night were well calculated to inspire confidence in Mr. Macindoe as a teacher of fashionable dancing.

It is clear from this review that skill in dance steps and excellence in etiquette had been thoroughly mastered under Mr. Macindoe’s instruction. His students were now prepared to take their place in polite society.

By the end of the 1850s trends in social dancing were changing. Advertisements in local newspapers announcing dancing assemblies became virtually non-existent, indicating that their popularity as fashionable entertainment had declined. Hamilton’s polite society was likely once again following the trend set in Britain, where it had become fashionable to attend large house parties featuring social dancing among other entertainments. In fact, Sophia MacNab, daughter of Sir Allan MacNab, wrote in her diary. “Aunt Maria gave us an account of the ball (at Dr. Hamilton’s) she said it was very pleasant and there were nearly a hundred people at it.”

Social dancing lessons continued to be popular, although the teaching repertoire was slanted more toward dance as recreation, and less toward its importance as dance as polite learning. Public ballrooms were opening in the city, and frequented increasing by Hamilton’s fast growing working class whose interest in dance leaned toward popular entertainment, rather than dance as polite learning. Dancing schools operating in Hamilton were teaching the most current and popular social dances, i.e. Polka, Bolero, Galop, Mazurka and the Sicillienne. It is possible that these new developments in social dancing were the reason for Mr. Macindoe’s sudden departure from Hamilton in 1856. A teacher of the old school, perhaps his particular teaching talents, which emphasized the learning of social decorum through dance, were no longer useful in the new, and more casual, recreational environment of the public dance hall.

Reading Guide

Elizabeth Aldrich. From the Ballroom to Hell: Grace and Folly in Nineteenth-Century Dance. (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1991).

Elizabeth Aldrich. From the Ballroom to Hell: Grace and Folly in Nineteenth-Century Dance. (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1991).

Freda Crisp, “Dance in Polite Society: Hamilton, Canada West (1840-1860).” MA thesis, York University, 1991.

Allen Dodworth, Dancing and Its Relations to Education and Social Life With a New Method of Instruction Including a Complete Guide to the Cotillion (German) with 200 Figures (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1888).