The Dancing Masters

Thomas Macindoe

Thomas Macindoe opened his dancing academy in Hamilton in 1846, and returned to the City on a bi-annual basis for a decade. His career is an excellent example of the importance of the dancing master to polite society both in Hamilton and throughout North America during the early and mid-nineteenth century. These teachers were perhaps Canada’s first cultural ambassadors as they travelled from town to town introducing the current ballroom dances, as well as social graces. Through their knowledge of etiquette they assisted the gentry in self-development through dance. The wider result of this awareness, it was hoped, would be the habitual use of politeness and consideration toward others in all social situations. Good manners were not only a sign of charity toward others, but also a sign of self-respect and maturity, a sign that one was ready to accept the responsibility of taking his or her place in society.

As is true of many of these early travelling dancing masters, biographical facts pertaining to Thomas Macindoe’s personal life are few, and there are also areas of his professional life that remain undocumented. Information obtained from Glasgow city directories seems to indicate that he was a native of Scotland who arrived in America early in the 1840s. Where, or with whom he studied dancing is not known.

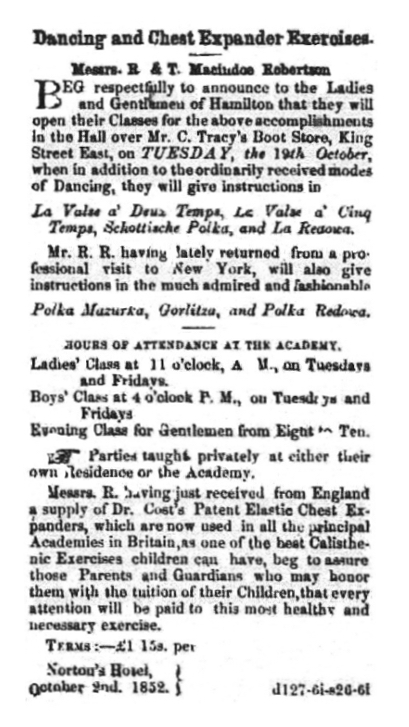

Macindoe’s first studio in Hamilton (1846) was located in a suite of rooms above the Mechanics’ Institute on King Street West. In 1852, he moved a few doors down the street to quarters over M. C. Tracy’s bookstore. His competence and popularity as a teacher of dancing and etiquette in Hamilton is confirmed by the fact that he continued to teach in the City for ten years (1846-1856).

His regular bi-annual teaching visits to Hamilton happened in the spring and autumn seasons. Each session consisted of a ten week term, and his busy teaching schedule indicates the importance of his services to the City’s upper class community. Young ladies studied Monday, Wednesday and Friday from one to four in the afternoon. Young gentlemen followed from five to seven in the evening. Gentlemen’s classes were taught from seven to ten at night on the above-mentioned days. Private family instruction and ladies’ seminars were held Tuesday and Thursday.

His dance teaching included the quadrille, polka, galop, contradances, cotillion and the waltz. All of the dances in Macindoe’s repertoire were popular in distinguished social circles in the United Kingdom, and consequently, in Canada.

In addition to dancing lessons Macindoe taught physical fitness to men and boys. The course consisted of Indian club exercises, and the use of Dr. Cost’s Patent Elastic Chest Expanders. Indian clubs and chest expanders kept the arms and torso in physical shape, and were recommended at this time as a splendid exercise for boys.

Another sign that his clientele consisted of the gentry is found in his Hamilton Spectator advertisements, which say that he taught private family instruction, ladies’ seminars, three lessons per week, and payment by the term. At the mid-nineteenth century only the upper class would have had the necessary wherewithal to commit to such lesson arrangements.

It is interesting that in all the years that Macindoe taught dancing in Hamilton, he never advertised the price of a term of lessons. It was only in 1852, when he brought physical education classes into his teaching schedule that a fee was listed. Advertising without a fee may have been prompted by the distaste prevalent among the contemporary upper class regarding the discussion of personal monetary issues. He was, after all, a teacher of polite learning, and to discuss money matters publicly would probably have indicated to the elite a lack of good taste.

John Bain

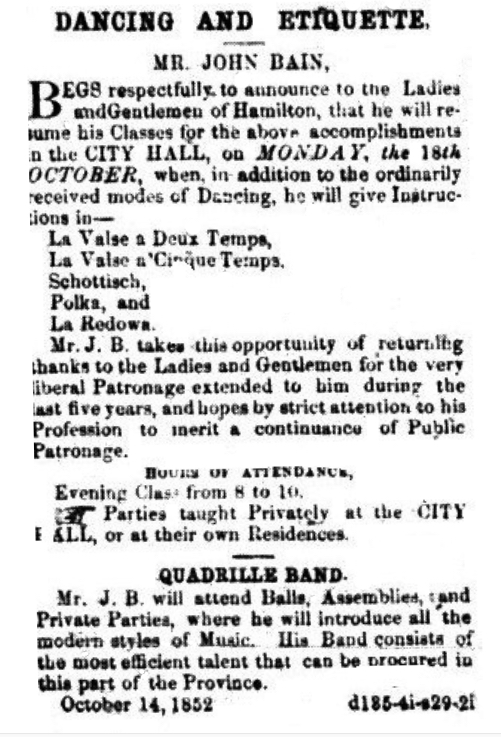

John Bain was a resident of Dundas, Ontario, a small town located a few miles west of Hamilton. Principally a musician, he made his living by teaching and conducting his own quadrille band at dancing assemblies and balls; where he studied dancing and with whom is not known. It may have been with Messrs. Fitch and Rodgers who taught dancing in Hamilton prior to 1846. In any case, in 1847 he began teaching dancing in Hamilton’s Town Hall on Saturday evenings. He continued to do so until 1853, at which time he discontinued the classes in order to devote more time to his quadrille band which was having increasing success throughout the county as an accompaniment to dancing assemblies and balls.

Bain’s career as a dancing master in Hamilton is of interest because it allows a glimpse into other facets of Hamilton’s cultural life at the mid-century, i.e. 1840-1860. The nature of his teaching repertoire indicates he drew his clientele from the working class. Through it we can learn something of how dance fit into the lives of people living in Hamilton who were not included in polite society. This repertoire included the Redowa, Schottische, Polka, La Valse à Deux Temps, and La Valse à Cinque Temps, which were dances associated with public ballrooms in Europe and the United Kingdom which were frequented mostly by working class people. Further, since he used his quadrille band to accompany his classes, his teaching approach was probably a combination of learning formal steps and recreational dancing. It is also notable that he charged for lessons on an individual basis, a procedure that seems to be more in keeping with an admission fee to a public ballroom, rather than an established dancing school where students paid by the term.

Students attending Mr. Bain’s dancing classes probably received the type of dance instruction criticised by Allen Dodworth, the noted New York City society dancing master as, “the introduction of novelties”. In his manual, Dodworth condemned the teaching of dance without the accompanying instruction in proper social decorum. It is doubtful that Mr. Bain covered the skills associated with proper social etiquette in depth. However, this does not mean that students attending Mr. Bain’s classes enjoyed the dancing any less than students who studied under Mr. Macindoe.

Mr. Hallet

Exactly when the Hallet family arrived in Hamilton is not clear, but his name appears in the local press as early as 1848, when he and Major Kelk formed a quadrille band for the purpose of playing at dancing assemblies. Later in 1848 he struck out on his own and with his own band took up the duties as the pit band at the Theatre Royal. In 1849, he and his family were living on Market Street East. One year later they relocated to Rebecca Street. In 1852 he went into the business of dance teaching one night a week at the City Hall. Like Mr. Bain, Hallet’s repertoire was geared to the working class. Using his quadrille band as accompaniment for his classes, he taught La Valse a Deux Temps, La Valse a Cinque Temps, Schottische, Polka, La Redowa, and Cotillions (Quadrilles).

Where Hallet acquired his dance teaching skills is another unknown, but his classes must have been successful, since in November of 1852 he organized a ball for his students. Strangely as of 1857, he is no longer advertising his dancing classes or his quadrille band in the Hamilton Spectator . No more is heard of him or his family.

Reading Guide

Elizabeth Aldrich. From the Ballroom to Hell: Grace and Folly in Nineteenth-Century Dance. (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1991).

Elizabeth Aldrich. From the Ballroom to Hell: Grace and Folly in Nineteenth-Century Dance. (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1991).

Freda Crisp, “Dance in Polite Society: Hamilton, Canada West (1840-1860).” MA thesis, York University, 1991.

Allen Dodworth, Dancing and Its Relations to Education and Social Life With a New Method of Instruction Including a Complete Guide to the Cotillion (German) with 200 Figures (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1888).