George and Emma Skerrett & Co.

In the summer of 1844, George and Emma Skerrett, eager to improve their professional credits, and probably their financial circumstances, immigrated to the United States from Edinburgh, Scotland where they had been regulars at the Edinburgh Theatre.

They both made their debut at the Park Theatre in New York City in September of the same year. Emma opened on September 3rd as Gertrude in James Robinson Panché’s The Loan of a Lover. George followed on the 14th playing the role of Dominique in The Deserter by Louis-Sébastien Mercier.

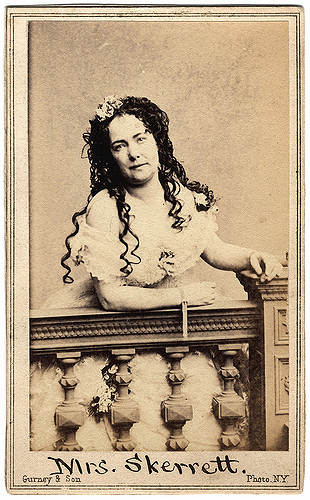

Emma was superior to George in acting skills and quickly earned a reputation as a soubrette of the brisk and mischievous type. This is verified in Ireland’s book Records of the New York Stage.

She played the character (Clara) well, but far exceeded it the same evening as Gertrude, in the “Lone of a Lover.” In a certain class of soubrettes, rustics, and mischievous boys, she has been particularly charming−witness her Minnie in “Somebody Else,” in which she has remained entirely unrivaled; her Marie in “Ernestine,” her Nan, in “Good for Nothing”; Tom Crop, Lazarilla, and her burlesque Aladdin. Entirely deficient in the expression of pathos or passion, she bit off the innocent simplicity of Jessy Oatland and Cicely Homespun with telling effect, and in the gayety and intriguery (sic) of Helen Worrett and Miss Hardcastle has seldom been excelled on our stage.

While Emma’s career advanced, George’s lagged; Ireland remarked that his poor health was responsible for his lack of professional progress.

Mr. George Skerrett was inferior to many well-known comedians, but was nevertheless respectable in his line. He was for years affected with a bronchial irritation, which seriously marred his professional efforts, and finally resulted in consumption, of which he expired at Albany, on the 16th May 1855.

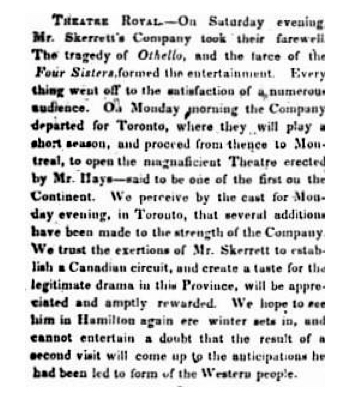

In 1845, following a short stay in New York, the Skerretts toured the southern United States as members of Noah Ludlow’s Troupe. Leaving the troupe in the spring of 1845, they departed for Montreal where George had accepted the responsibilities as lessee and manager of the Royal Olympic Theatre. The industrious couple had started a small summer touring circuit by 1847 that included the new Theatre Royal in Hay’s Market in Montreal, as well as, theatres in Kingston, Toronto, Hamilton and Albany, New York.

When the company arrived in Hamilton in May of 1847, George had already leased the Theatre Royal. However, the season got off to a poor start when the opening night’s performance on May 10th was cancelled due to a heavy rain storm. According to the May 15th edition of the Hamilton Spectator, performance attendance was probably not what Skerrett had anticipated, prompting him to run the following advertisement in the paper.

Mr. Skerrett respectfully announces that the patronage hitherto bestowed on the Theatre not defraying the nightly expenses he is compelled abruptly to terminate his season, and trusts, during his limited stay, those favorable to a well conducted drama will honor him with support, to render his loss less enormous, and his anticipation of a future visit more agreeable.

Attendance must have improved since the company finished their Hamilton season on July 7th, and continued their tour plans by alternating weeks between Hamilton and Toronto’s Mirfield’s Lyceum Theatre. The company then moved on to Kingston where they played a few nights before returning to Montreal.

For the Skerretts, and other companies, these summer tours played an essential part in keeping them financially stable. They were a means of bringing in added revenue that would be needed to produce the winter season when it was impossible to tour due to the poor road conditions. However, the tours were not without hazards. A wagon breakdown while on the road or poor weather conditions could cause performance cancellations, which inevitably put the company into financial difficulty. Whenever Skerrett leased a theatre, like other theatre managers of the era, he took on the responsibility of presenting that theatre’s sole entertainment for the specified period of the lease. Under these circumstances it was vital to have regular, well attended and regular performances in order to meet his financial obligations, which entailed booking acts, paying performers, assembling a core of technicians, looking after advertising and the general management of the theatre while the troupe was in residence. In addition he chose the playbill and directed the plays.

What procedure Skerrett followed regarding financial remuneration paid the members of his company personnel is not known since no existing criteria in the form of daily or monthly records have been located. If he followed the standard of the era then his employees were probably paid in one of two ways: share-holding or salary-benefit. Share-holding meant that each member of the company received a share or part share of the box office receipts after expenses. Established companies were paid under the salary-benefit system whereby each member of the staff received a stipulated weekly salary. Featured players with the company received extra remuneration in the form of a benefit performance which gave them a share of the box office receipts.

By December of 1849, the Skerretts had given up the management of the Montreal theatre and were once again in New York City acting at the Broadway Theatre in the Four Sisters. They remained in New York until the summer of 1851 when they returned to Montreal where George had leased the Garrick Theatre. The Garrick was a very small theatre under the control of the Garrick Club, an organization of amateurs who, like the members of the Hamilton Amateur Theatrical Society, were all vitally interested in theatre. When Skerrett moved into the Garrick it became affectionately known as “Skerrett’s Band Box” because of its miniature size and the small three piece orchestra engaged by him. The Skerretts stayed in Montreal for some time and then dropped out of sight. Their departure may have been associated with George’s deteriorating health. Ireland says that George died from consumption at Albany, New York on May 17, 1855. Shorty after her husband’s death Emma married Harry L. Bascombe from whom she separated in 1857. She died in Philadelphia on September 27, 1887.